Collector Stories

Camondo and Kraemer,

a long and beautiful story between collectors

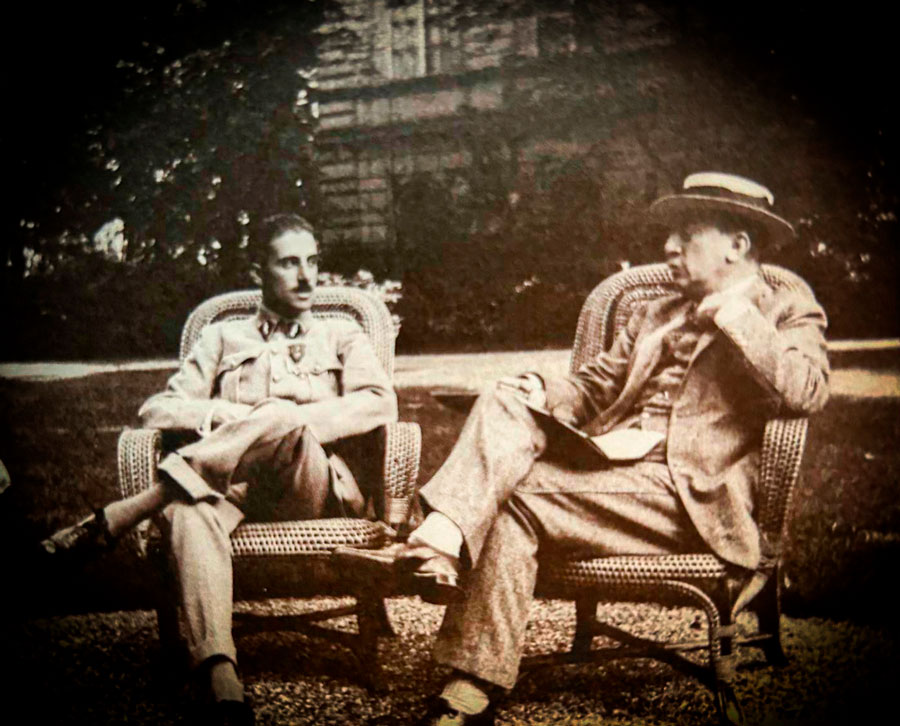

On September 5, 1917, Lieutenant Nissim de Camondo, son of Comte Moïse de Camondo, went missing on an aerial mission while conducting photographic reconnaissance over the front between Germany and France.

As we pay tribute to the heroes of the First World War, the Kraemer family remembers with great emotion the very special bond established with their neighbors on Rue de Monceau.

Galerie Kraemer has a special relationship with the Nissim de Camondo Museum.

This renowned family of art collectors were neighbors, clients, and friends.

We were therefore honored and moved to write them these few words.

Dear Camondo family,

Our two families first met at the beginning of the 20th century.

We are more than just neighbors at 43 and 63 Rue de Monceau in Paris.

Friendly bonds were woven between collectors and antique dealers.

Your family, along with our great-great-grandparents, great-grandparents, and grandparents, inspired and created an art of living that has since become legendary.

Thank you for preserving your ancestral traditions of generosity and humanity wherever you resided.

Thank you for being great patrons of France and French art.

Thank you for being a benchmark for great collectors from your time to ours.

And more humbly, thank you for contributing to the rise of Galerie Kraemer, which is deeply honored today to participate in the restoration of your beautiful residence.

Thank you, Camondos.

The Kraemer family.

Renovation of the kitchens and bathrooms of the Nissim de Camondo Museum.

The Committee for Camondo.

Created in 1985 by patrons, the committee enabled the restoration of several rooms and salons so that the Camondo home could regain its former splendor.

The Kraemer family also contributed to the renovation of the superb kitchens—certainly the only ones of their kind visible in Paris—and the bathrooms of the Nissim de Camondo Museum, which reflect the workings of a grand Parisian residence from the early 1900s.

Galerie Kraemer has also supported exhibitions held at the Nissim de Camondo Museum, such as those on the bronzesmith Jean-Louis Prieur and the silversmith Robert-Joseph Auguste, two great artists of the 18th century.

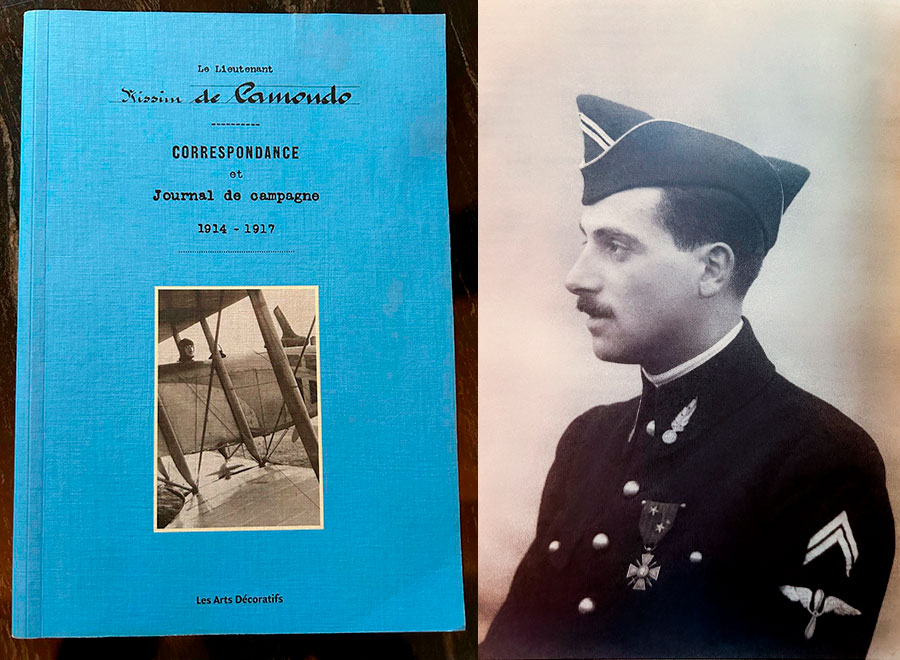

We also had the pleasure of contributing to the exhibition “Nissim de Camondo and the Great War 1914–1917,” as well as to the publication gathering his correspondence with those close to him, particularly with his father.

Nissim de Camondo, Correspondence and Campaign Journal. 1914-1917 and Portrait.

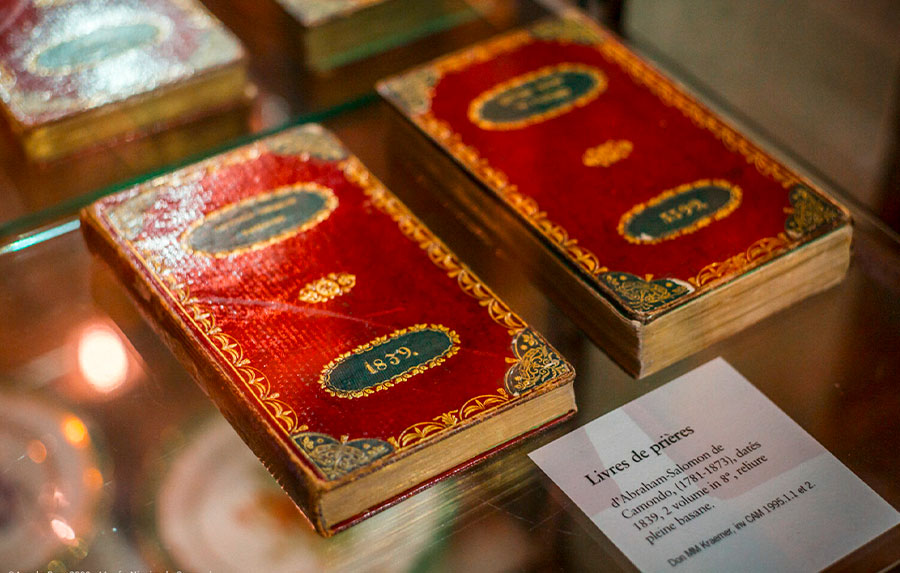

Symbolic objects in the Camondo Museum.

Few clues in the museum indicated to visitors the religious origins of the Camondo family.

We discovered two prayer books that once belonged to the Camondos, one for Rosh Hashanah and another for Yom Kippur, published in 1839 in Vienna and bound in Constantinople with multicolored mosaic leather bindings.

The name of Abraham Salomon Kamondo is distinguished in both Hebrew and Latin letters.

When we shared with the museum curator our wish to offer them, she kindly reminded us:

“Laurent and Olivier, you know very well that no objects can be donated to the Camondo Museum, it’s in the will.”

We told her of our intention that, whatever happens, these books would never leave Rue de Monceau, whether at 43 or 63.

It was difficult, amidst the emotion of the meeting, to remember whether it was she or we who found the solution…:

It will therefore not be a donation, but a simple return!

Having simply “returned” them, these books are now displayed in a showcase in a room near Nissim’s bedroom on the second floor, alongside other private objects, some of which we later found, and family photos.

These rare books remind visitors that the Camondo family was lost at Auschwitz.

Without their generosity, and thanks to the donations to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD), their mansion, and of course their collection, the name of those once called the Rothschilds of the Orient would have been forgotten.

The fascinating book by Pierre Assouline, Le Dernier des Camondo (Gallimard, 1997), along with other beautiful works, has truly helped to revive this museum, which had somewhat fallen into slumber.

Until today, thanks to high-quality curators and the dedicated museum staff, visitors feel as though they are welcomed into a fantastic private space, which the ongoing renovation will make even more appealing.